I’m white-knuckling the steering wheel as my thirteen-year-old son fumes in the front seat beside me. We turn south out of the city library’s parking lot. His words flatten me like a leaf between the pages of the complete works of Shakespeare.

You can’t force me to like books!

The trip to the library has been another futile attempt to pique his interest in books, stories, and my favorite pastime: reading. Who wouldn’t want to spend an hour browsing through shelves and shelves of titles?

My son, that’s who.

My constant nagging, the forced family reading sessions, my shopworn assertion that reading is the antidote for boredom—it has all backfired. Big time. This is the mammoth of all my parental failings. My two adult kids confess to hiding in the garden corn on summer mornings just to avoid reading time. And although my oldest daughter now reads the classics, no one reads like me. Devouring book after book like a Netflix binge of Stranger Things.

“I hate books,” Zeke adds, delivering the final karate chop to our jury-rigged match.

He’s no son of mine! I seethe silently. He will be a fool all his life, without vision and imagination. And without imagination, Anne Shirley informs us, “How much you miss!” But try installing such a notion into the brain of a thirteen-year-old. It’s like trying to plant a seed in your granite kitchen countertop.

No doubt I am partly to blame for my children’s flimsy bibliophilic-bones. I never read picture books to my pregnant hump or told theatrical stories in Jim Dale voices at bedtime. On those lazy summer mornings, I often left my kids hiding in the corn or allowed the TV to blare for hours in the afternoon. And I failed to pass down, for a variety of vanilla reasons, one of my most cherished childhood traditions: the habitual trip to the library.

Every three weeks, my mom toted my siblings and me to the Orem Public Library. I don’t remember if attendance was mandatory, but I anticipated it as a rule of family law, like the 80 degrees requirement my mother established before we could don a swimming suit and run through the sprinklers. There was a consistency that draped my mom’s character, like medieval robes, and so we went, in the canary-colored station wagon, to the bricked building every third Saturday morning.

Once inside, I flew to the shelves that housed my favorite authors. For a time, I chose one book from each of my favorites. A Nancy Drew adventure, a Boxcar Children, and a Beverly Cleary. Maybe an Anne of Green Gables or the next in line from the Oz series. The librarian stamped each book and pushed the stack across the desk to my greedy hands. In the following weeks, I devoured all the books while sprawled on our green shag carpet, perched in one of our cherry trees, or burrowed in the double bed I shared with my sister. Only now do I realize how rare it was for any child to do this much reading, even back in the 1980s before Xboxes, Netflix, and smartphones.

I took my cues about the world from the stories I read.

Nancy Drew conjured up mystery in my everyday life, leading me to find intrigue in random objects: a page of stationery, a diary, a wooden statue. My collection of rinky-dink knickknacks on the shelf above my bed became clues to century old secrets.

In a house of eight children, I mined for a place of my own and an abandoned boxcar seemed the idyllic hideaway. “What a good place this is! It is just like a warm little house with one room!” said Violet. In The Boxcar Children, adventure foxtrotted with quaint and cozy. The children extracted dishes from the nearby dump, a wounded dog showed up in need of love, and the tiny waterfall in the nearby brook cooled the bottles of milk Henry bought in the neighboring town. They fashioned beds out of pine needles and a broom out of sticks. The ache for the boxcar experience lodged in my stomach like molasses. I wanted to be those children, living those doltish adventures with effortless outcomes.

With Anne of Green Gables, it was love at first sight. She gazed up at me from the cover of the book that lay haphazardly on the corner of the library table. Surprisingly, I’d never heard of the tale before. But in an impulse that can only be attributed to fate, I chose it over all the other titles. My mom would pay for only one book from the school’s annual book fair, and I selected Anne spelled with an E. A few pages into the story, I realized the girl could talk. During that first carriage ride with Matthew, she prattled on for five pages about the horrors of the orphanage, and her imagination, and the red roads and white blossoms, and her red hair as her “lifelong sorrow.” Her uninhibited candor fascinated me, tongue-tied as I was at the time, and although I often rolled my eyes at her idiosyncrasies, I secretly loved her for each and every one of them.

From Prince Edward Island, I catapulted straight into other realms and worlds. The land of Oz breathed stranger and more vivid than even the eyepopping technicolor in the classic movie. As it turned out, Dorothy and her troupe’s journey to the Emerald City constituted only a fraction of the story, and the series brought to life a plethora of characters with psychedelic names like Button-Bright, Jellia Jamb, Woggle-Bug, Shaggy Man, and the endearing Jack Pumpkinhead. In the shenanigans of these characters, I harvested such overarching themes as goodness and patience rewarded, deceit and cruelty punished, and redemption for the outcasts.

My dad faithfully read us the Chronicle of Narnia until Narnia became a second home to me. The endless winter, the white witch, the lion’s sacrifice. I went with Lucy to the lamppost, to Mr. Tumnus’ home. I ate Turkish delight with Edmund, even though I seriously questioned how candy made from turkey meat could tempt anyone. I remember the cadence of my dad’s voice and the eerie thrill lodged in my throat when we reached the dark island in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Hidden in an inky fog, this land fostered dreams. But not daydreams, mind you. No, the dreams that made you afraid of going to sleep again. The dreams that no man could face. I joined the cast of characters heaving on the oars of the ship in retreat. We rowed like spooked banshees back toward the light.

As a young teen, I read The Witch of Blackbird Pond in one gulp, sensing a similar animosity in the hallways of Canyon View Junior High. The obnoxious behavior of the kids in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory disturbed me more than the creepy Oompa Loompas, and The Diary of Anne Frank dropped me directly into the depraved waters of World War II as if I’d been sitting unknowingly on the precarious seat of a dunking machine.

The Outsiders stirred me to distraction in the same way the movie Dead Poet’s Society would years later. Even though my life lacked the teenage drama crammed in these stories, I swallowed the themes as gospel: the evils of conformity, the sacrosanctity of friendship, and the poetic underpinning in all adolescent adventures. I ached to be a part of the story, to be the one to say: “Thanks, Ponyboy. You dig okay.”

In high school, I devoured Jane Eyre with hormonal intensity. Besides having all the elements for a great story—a destitute orphan, a cruel aunt, an abusive boarding school, a haunting estate in the English countryside, and a horrible secret in in the attic—it was the notion that a plain, homely woman could get the guy by something called rich individualism that thrilled me.

I, too, was poor, obscure, plain and little. I, too, had soul! I had heart!

In this way, I trumped the popular blondes prancing the halls of Orem High School because I was plain, unassuming, and hid my real character under bad hair. Someone like Mr. Rochester would pick me over them just like he picked Jane over the luscious Blanche Ingram. I believed that despite my banana clip and pegged pants, my love would show up on a dark and rainy night, with a tragic backstory and impassioned feelings.

While waiting for Mr. Rochester, I read My Name is Asher Lev, a poignant tale with a different kind of love dilemma. The impasse between Asher Lev’s orthodox religion and his artistic gift caused serious conflict, the kind William Faulkner describes as “the human heart in conflict with itself.” Although I had no such inner struggle at the time, I latched onto the pathos of the story enough to write one of my pathetic poems in honor of Asher Lev: Born with a gift/He could not hide. Born with a gift/That would never die.

Loneliness followed me into college like a shadow without form, and when I read Frankenstein in British Lit and shed the nuts-and-bolts Frankenstein monster of my youth, I identified with this new sensitive guy. A congenial chap, really, who watched the cottage inhabitants until his need for connection drove him from his hiding place. Of course, when they saw him, all was lost. His was the ultimate outcast story.

There is no doubt my book addiction has bred some hardcore magical thinking at times, especially when it came to relationships or vacations or how certain clothes would make me feel when I wore them. It’s tempting to avoid real life with the easy voyeurism available in fiction. For a long time, I believed life happened without any effort on my part. A Stan Crandall would appear in my life at the age of Fifteen or a Pa-like character would always turn up to build that log cabin or play his fiddle when I needed a pick-me-up. And because of stories, I believed romantic love would look a certain way when it appeared, so I questioned it when it turned up too normal and dressed in a T-shirt.

But when life dolloped a doozy that discredited all fairy tales, I found answers in the written word, a place where tragedy always serves a purpose.

When I struggled to find words, any words, for a friend who’d just lost her two-year-old son to cancer, I copied this line from The Poisonwood Bible:

“As long as I kept moving, my grief streamed out behind me like a swimmer’s long hair in water. I knew the weight was there, but it didn’t touch me. Only when I stopped did the slick, dark stuff of it come floating around my face, catching my arms and throat till I began to drown. So I just didn’t stop.”

Yes! She wrote back. That is about right.

When my British fiancé abandoned our religious faith, I returned to Asher Lev and his tormented mother who grappled between her love for her only son and her consecration to God:

“Trapped between two realms of meaning, she had straddled both realms, quietly feeding and nourishing them both, and herself as well. I could only dimly perceive such an awesome act of will. But I could begin to feel her torment now as she waited.”

Her dilemma was my dilemma. She knew she could not nourish both forever, that when a heart straddles two opposing loves, the heart will eventually crack. Others wondered at my misery and questioned why I put principles over love. But Rivkeh Lev understood. She knew there were limits even to love.

Together, we waited as sisters-in-grief for our hearts to break.

And when my mom passed away, I found strange comfort in The Elegance of the Hedgehog, a novel about a Parisian apartment building full of inconspicuous tenants with idiosyncrasies and quiet victories. The words on the page quieted my world like healing stones on my spine.

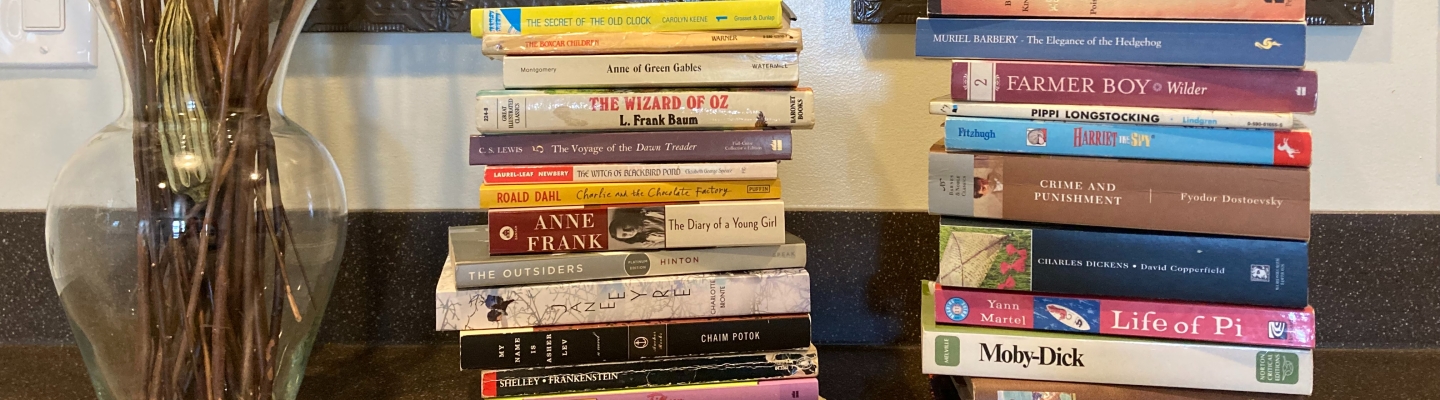

Driving home from the library, I glance at the pale, stormy face of my son and wish for words, any words, that might plant my love of reading into his fledging mind. If only I could give him a proper introduction to Almanzo Wilder, Pippi Longstocking, Harriet the Spy, and Aslan. In a few years, I want him to hobnob with Raskolnikov, David Copperfield, Pi Patel, and “call me Ishmael.” But he’s thirteen and doesn’t want to meet any of my friends.

I hear Jane Eyre chiding him for his lack of study. “No. This will not do. What about your character, sir? How do you suppose to understand the world outside your small influence?” From the depths of MacDougal’s cave, Tom Sawyer taunts him, “Why don’t you read? Is it because you’re a coward? Start reading or suck eggs!” And Jonas, the Receiver of Memory, stands in a room with a thousand books lining the walls, books that contain the memories of the whole world. He beckons wildly for Zeke to join him:

“Without books, we live in sameness without the capacity to see beyond. And trust me, Zeke…

You will want to see beyond!

Your descriptions and book/quote choices were beautiful and meaningful in my life was well. You have expressed my life with my younger children so perfectly. Thank you for such a lovely read today. Love you!

Sent from my iPhone

>

You are an incredible writer, Kristen! I love reading anything you write! Thank you for sharing your talent!

Oh I love this!! Reading was such an out for me too – I loved our trips to the library! I was just remembering how excited I would get when the book orders arrived at school😄

Thanks for bringing back memories and reminding me of when I gained my love for books! A cherished memory from our childhood…

Keep writing Kris – you are so talented. Love you❤️

Sent from my iPhone

>

Thank you for expressing so well a love of books and how they help, heal, and inspire! I hope my girls find the same love for books!

This is a wonderful essay, Kristen! I also love these books, but I haven’t read every one, so I’m jotting down a couple for my future. I just finished listening to Crime and Punishment. I find books bring so much enjoyment into my life.